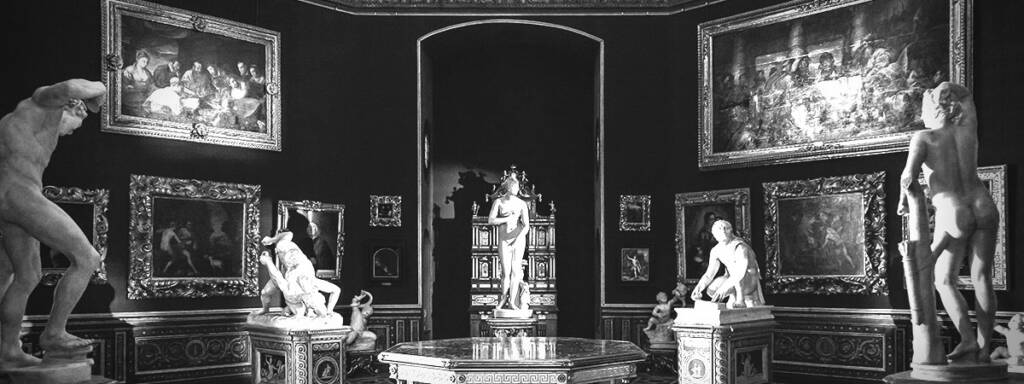

Marta De Bortoli – Tribuna Uffizi

The Medici story is often told as a tale of splendour, genius, and political intrigue, but beneath the familiar narrative lies something far more instructive for anyone studying multigenerational enterprise. For three centuries, the family moved through three distinct identities: bankers, princes, and finally cultural stewards. A different attitude toward capital, governance, and succession characterised each phase.

The dynasty began as a carefully engineered financial system designed to diffuse risk and preserve control. It expanded into a political machine that governed Florence without ever admitting to monarchy. It ended as a custodial project, with the last heir converting private treasures into a public trust that would outlast the bloodline itself.

By following the succession line step by step, this case study traces how governance, character, and context shaped one of history’s most influential families. It also shows how the choices of each generation contained the seeds of both continuity and collapse.

The Architecture of Ascendancy

The Medici story begins not with dukes or popes, but with a cautious, methodical banker. Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici (G1, 1360–1429) founded the Medici Bank in Florence in 1397. He entered a market still marked by the failure of Siena’s great houses and the earlier collapse of firms like the Peruzzi and Bardi. Those failures were an education in what not to do: overexpose yourself to kings, concentrate risk, and run everything through one legal entity that can be brought down by a single bad debtor.

Giovanni’s response was both conservative and inventive. He built a system designed to spread risk, protect control, and keep the family’s options open. The Medici Bank was a web of legally distinct firms: a central partnership in Florence and satellite partnerships in Rome, Venice, Geneva, Bruges, London and selected industrial ventures in wool and silk. Each operation had its own capital, its own participants, and its own accounts.

From a distance, this looks remarkably like a proto holding-company model. The Florentine partners sat at the centre, co-owning and coordinating a portfolio of operating firms rather than pushing everything through one balance sheet. If the London branch failed, it would not automatically drag down Florence or Rome. In theory, the family could cut off a diseased limb to save the body.

The price of this protection was managerial. Legal separation worked only as long as the Florence partners kept tight oversight over the branches. The system depended on constant scrutiny of the men on the ground: partners and managers who had both authority and the temptation to take risks that Florence could not easily see.

Giovanni’s genius lay in accepting this tension and choosing prudence as his personal discipline. He stayed close to the core accounts, resisted a showy office, and built the kind of reputation that made conservative clients comfortable. His political stance matched his banking: he supported taxation reforms that eased the burden on the poor and avoided the grand offices that would have made him a target. He understood that, at this stage, visibility was risk.

Financial Instruments as Regulatory Loopholes

The Medici did not invent every tool they used, but they were early and systematic adopters of methods that allowed money to move faster. Two innovations mattered most:

Double-entry bookkeeping allowed for more accurate tracking of capital across a dispersed network. Debits and credits were recorded in a way that gave the Florentine partners a coherent view of distant operations. It made it possible to see patterns and trouble in time.

Bills of exchange turned the Bank into a transfer engine rather than a simple hoard of coins. A merchant in London could pay in one currency; a partner in Florence could pay out in another. Time, distance, currency and credit risk were all priced into a neat, portable document.

These instruments were also politically and morally useful. Canon law formally condemned usury. The Medici needed to earn a return without calling it interest. The solution lay in exchange. Instead of lending 100 florins for 110, the Bank could issue a bill payable in another city at a different rate. The difference between what went out and what came back was framed as an exchange margin rather than an interest payment. In other cases, goods could be sold at skewed prices, embedding the finance inside trade. Profit came from “exchange” or “discount”, not from a naked interest rate.

Giovanni’s approach to these tools was controlled and calculated. The Medici Bank became known as a house that could move money quietly across Europe, without flaunting the theology it strained.

Securing the Papal Account

In 1420, the Medici became Depositors of the Apostolic Chamber, effectively treasurers and transfer agents for the Roman Church. This single relationship changed the scale of the Bank. The Papacy collected revenue from across Europe and needed a partner that could receive, convert and remit funds through multiple jurisdictions. The Medici were now not just another Florentine firm: they were the financial arm of Latin Christendom.

The Papal account conferred three advantages:

- Profit and fees: regular flows from tithes, indulgences and other collections.

- Prestige: association with the Church gave the Medici moral cover for their wealth and methods.

- Political leverage: the family could now call on Papal authority in disputes, and remained close to the evolving doctrine on interest and lending.

This relationship, however, altered the risk profile of the Bank. To serve the Papacy and its clients, the Medici increasingly extended large, unsecured or weakly secured loans to sovereigns and nobles. Royals needed cash to wage war, marry, and build. The Papal umbrella made these arrangements easier to justify, but did not make the borrowers any more reliable.

What Giovanni built was therefore a paradox: a system designed to compartmentalise risk, whose most profitable client pulled it towards concentrated exposure on the most dangerous counterparties in Europe.

From Prudence to Spectacle

When Giovanni died in 1429, he left his son, Cosimo de’ Medici (G2, 1389–1464), more than a bank. He passed on a profitable network of partnerships capable of rapid growth, a hard-won reputation for reliability, and a single, towering client in the Papacy whose needs alone could bend the balance sheet.

Cosimo inherited both the architecture and the structural vulnerability. He also inherited a choice: keep the family as wealthy, discreet merchants, or use the financial engine as a launchpad into politics. Cosimo chose the second path.

His first major succession test came in a crisis. In 1433, his rivals engineered his exile from Florence on charges of aspiring to tyranny. Within a year, the political winds shifted; Cosimo returned to the city in triumph. From 1434 onwards, he became the undisputed gran maestro, the quiet conductor of the Florentine Republic.

Crucially, he did not take a royal title or abolish republican forms. The councils stayed in place, elections continued, and laws were passed in the city’s name. Cosimo governed through influence, not formal office. He placed allies on key councils and made sure that critical decisions aligned with Medici interests.

The key tools of this “governance by subversion” were institutional:

The Scrutinio (electoral process) could be steered through patronage and pressure, ensuring friendly names emerged from the bags at the right moments.

The Catasto (tax registry) became a subtle instrument of reward and punishment. Supporters could find their assessments softened; opponents might discover a new and heavier burden.

In practice, this meant that holding office in Florence became increasingly correlated with being inside the Medici orbit. Economic and political fortunes fused. Wealth flowed to those who were aligned with Cosimo’s network, creating a closed loop of loyalty and influence. The line of succession from Giovanni to Cosimo therefore marks a decisive shift: while Giovanni built financial capital, but avoided high office, Cosimo the Elder used financial capital to influence the state while maintaining the appearance of republican continuity.

Patronage as a Strategic Investment

Cosimo understood that rule by subversion could not rest on fear or patronage alone. It needed a story: a Florence made more beautiful, more prosperous through the Medicis’ systematic cultural investment.

Cosimo financed or supported:

- Brunelleschi’s dome for the Cathedral transformed the skyline of the city.

- The rebuilding of San Lorenzo, which became both a parish church and a Medici monument.

- Libraries, academies and the collection of classical manuscripts, positioning Florence as a centre of humanist learning.

- Artists and sculptors such as Donatello, whose works adorned both sacred and civic spaces.

These were long-term investments in reputation. The family’s money became visible as a public good, softening resentment about their influence and helping to legitimise their growing control.

Patronage also had a practical financial function. A city filled with artists, scholars, and visiting merchants needed credit and exchange services. Cosimo’s Florence became both a theatre of culture and a marketplace, where the Medici Bank sat conveniently at the centre.

Where Giovanni had used prudence and a low profile to stabilise the family, Cosimo used visibility and spectacle to cement their status.

Transitional Stewardship, Cultural Zenith and Commercial Erosion

Cosimo’s later years were spent managing both the Bank and a complex political network. By the time he died in 1464, he had two sons: Piero and Giovanni (the younger; not to be confused with Giovanni di Bicci). Giovanni predeceased him, leaving Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici (1416–1469) as the main heir.

Piero, known as “the Gouty” because of chronic illness, inherited the Medici Bank still tied closely to Papal business, a set of international branches whose fortunes varied widely, and a political regime that relied on finely balanced loyalties and resentments.

He did not have his father’s stamina or his grandfather’s hard-edged commercial training. His tenure was marked by fragile health and a short time. In these circumstances, his stewardship was defensive rather than potent. He guarded what he could, honoured existing commitments, and tried to hold together both the Bank and the political coalition.

Piero’s most important contribution to the succession story was continuity. He ensured that the Medici regime did not collapse on Cosimo’s death and that a clearer heir could be prepared. That heir was his son Lorenzo de’ Medici “the Magnificent”, groomed from youth not only as a banker, but as a poet, diplomat and civic figure.

By 1469, when Piero died and Lorenzo took full control, the Medici structure stood at its zenith: a powerful bank with deep Papal ties, a city effectively governed from the Medici palace, and a family name synonymous with Florence itself. The next phase of the succession story shows what happens when this architecture is run by a leader whose attention is increasingly consumed by politics and culture rather than financial discipline.

Lorenzo de’ Medici assumed leadership at just twenty years old. He inherited a vast enterprise: the Bank, the political apparatus built by Cosimo, and a cultural network that was already attracting Europe’s finest artists. It was a fortune in every sense: financial, political, and reputational. But it was also a structure that needed constant scrutiny.

Lorenzo did not lack talent. He was charismatic, eloquent and intellectually gifted, a poet as comfortable with a quill as with diplomacy. His presence made him beloved by many Florentines and respected by rival courts. His problem was not ability, but allocation: his attention flowed towards the arts and the state, not the commercial machine that funded both. This shift in priorities marks the beginning of the Medici’s commercial decline.

The Executive Distraction Crisis

While Giovanni and Cosimo had treated the Bank with dedicated focus, Lorenzo viewed it as one of many instruments for Florence’s glory.

Three forces intensified this distraction:

Political pressures after the Pazzi Conspiracy (1478)

The attempt to assassinate Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano inside the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore plunged Florence into turmoil. The aftermath required constant negotiation with other Italian states and the Papacy. Lorenzo became a full-time statesman.

The weight of artistic and civic patronage

Michelangelo, Botticelli, Verrocchio, and a generation of humanists were under Medici protection. Lorenzo cultivated this cultural flowering with enthusiasm, commissioning works and hosting philosophers without fully acknowledging the strain it placed on the treasury.

The invisible complexity of the Bank’s risk profile

Branches in London and Bruges extended heavy credit to monarchs and dukes whom the Medici could not effectively pressure. The more Florence relied on Lorenzo’s political presence, the less attention the Bank received.

The Medici Bank, by design, depended heavily on the judgment of the Florence partners. It was a decentralised network that required centralised discipline: branch managers needed guidance; political borrowers needed boundaries; and distant partners needed oversight. Lorenzo, engaged constantly in diplomacy, festivals, public ceremonies, and cultural patronage, could not sufficiently provide these.

By the mid-1470s, two of the most important northern branches were failing.

London (collapse in 1478)

The English crown had long been a valued client. Edward IV enjoyed Medici credit and patronage, but the royal finances were often unstable. When the monarchy defaulted, the London branch was left with large, unrecoverable loans. Because the branch operated as a separate partnership, the direct impact on Florence was limited but still damaging.

Bruges (collapse in 1478)

Bruges was at the heart of northern European trade. Its clients included Charles the Bold of Burgundy, whose ambitions exceeded his solvency. The branch’s exposure to him proved fatal. As with London, loans were extended less on commercial criteria than on political opportunity.

Bruges and London shared the same flaw: credit decisions increasingly reflected diplomacy rather than banking discipline.

These failures coincided with Lorenzo’s growing preoccupation with holding Florence together after the Pazzi affair.

One of the least visible, yet most damaging, developments under Lorenzo was the quiet merger of public and private finance. The Bank was repeatedly used to advance funds for public ceremonies, defence, diplomacy, and civic works. In theory, Florence remained a republic with its own treasury; in practice, Lorenzo’s personal fortune and the Medici Bank were used as buffers for state liquidity.

This meant that the Bank’s reserves were tied up in Florence’s political obligations, often without proper repayment; losses from political loans were masked by flows between public and private accounts, and the family’s wealth became increasingly illiquid, committed to artistic commissions, festivals, and diplomatic expenses.

Lorenzo’s vision for Florence was expansive, imaginative and culturally transformative. But funding that vision required a level of financial discipline that the Bank could no longer supply. The structure that Giovanni had built to separate risk was now blurred by the family’s political entanglements.

“The Unfortunate” Successor and the End of a Chapter

When Lorenzo died in 1492 at the age of forty-three, the Medici still held Florence. The Bank was weakened but not yet in formal ruin, and the political machine remained intact. Yet beneath the surface, the foundations were crumbling.

Lorenzo’s son, Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici, called “The Unfortunate”, succeeded him. Piero lacked both his father’s charisma and his grandfather’s caution. His succession marks the moment when structural weakness and political miscalculation converged. Florence was under pressure from France, and the Bank was hollowed out by decades of losses and illiquidity.

The crisis erupted swiftly, in a cascading order:

- Foreign pressure: Charles VIII of France invaded Italy with the aim of marching to Naples. Florence, caught between alliances, was vulnerable.

- Miscalculated capitulation: in a bid to save Florence and himself, Piero conceded to French demands without securing the approval of the city’s ruling councils. This was viewed as cowardly and disgraceful.

- Public revolt: anger at Piero’s submission ignited riots. The Medici palace was sacked, and the family was expelled from Florence.

- Commercial collapse: without Medici political protection or credibility, the Bank’s hidden losses surfaced. Branches closed; capital had already been drained; sovereign debts were uncollectable.

By 1494, the most powerful bank in Europe ceased to exist. The Medici were no longer bankers. They were exiles. The next generation would regain control of Florence not with florins, but with Papal tiaras.

Rebuilding Power Through the Church

The collapse of the Medici Bank and the expulsion of the family in 1494 could have been the end of the dynasty. The political network built by Cosimo and Lorenzo evaporated almost overnight. Yet the Medici were not finished. They shifted their strategy from commercial capital to spiritual capital, drawing on a resource Lorenzo had cultivated without fully realising its future importance: their influence in Rome.

In a pivot that saved the dynasty, two members of the fourth generation would become popes. However, this was the result of decades of calculated political manoeuvring, social engineering, and the deliberate placement of family members inside the Church’s most influential circles. Lorenzo de’ Medici understood that Florence alone could not guarantee the family’s future. He therefore invested heavily in Roman networks — financing cardinals, cultivating curial officials, and positioning his son Giovanni for a clerical career from childhood. Giovanni received the cardinal’s hat at just 13 years old, thanks to immense diplomatic pressure and generous Medici financial support to the Vatican.

Elected pope in 1513, Giovanni — now Leo X — brought Medici patronage and Florentine sensibilities into the Vatican. His papacy was marked by lavish spending, artistic commissions, and widening political networks. But his greatest contribution to the family was strategic. He used his Papal power to restore the Medici rule in Florence. The city had oscillated between various republican and anti-Medici factions after 1494. In 1512, with Papal and Spanish support, the Medici returned to Florence as leaders once again.

It was a remarkable re-entry: a family that had lost its financial engine rebuilt its state through spiritual authority.

Giulio de’ Medici, elected Pope Clement VII in 1523, inherited a complex world marked by the Reformation, rising European powers, and tension between France and the Holy Roman Empire. His papacy saw two defining events for the family. He had been raised within Lorenzo’s inner household after his father’s assassination, absorbing the political craft of the Florentine court. His rise was supported by the Medici restoration in Florence, the broader influence of Leo X’s pontificate, and the continuing power the family held over factions within the Curia.

The Sack of Rome (1527)

Roman streets were overtaken by imperial troops. Clement fled in disguise. The Medici position seemed fatally compromised.

The Siege of Florence (1529–1530)

Anti-Medici Florentines attempted once more to restore the republic. But Clement VII secured imperial support. After a brutal siege, Florence surrendered.

The 1530 settlement engineered by Clement and Emperor Charles V abolished the old republican system and reinstalled the Medici as hereditary princes. The transformation was complete. The family that once governed Florence by subtle influence now ruled by imperial decree. Papal Medici influence created the conditions for the grandest succession shift in the family’s history: the elevation from financial power to monarchical sovereignty.

The Grand Ducal Line

With the republic defeated, the key question became: who would lead Florence?

The senior line of the Medici (descended from Lorenzo the Magnificent) was weakened. The solution was found in a cadet branch: Cosimo I, aged only 17, descended from a minor offshoot of the family through Giovanni delle Bande Nere.

To everyone’s surprise, the young man proved exceptionally capable and quickly moved from figurehead to effective ruler. He restructured the state, disbanded opposition, and centralised authority with a decisiveness not seen since Cosimo the Elder. Where earlier Medici had relied on influence, Cosimo I used formal power.

He achieved three defining milestones:

- Duke of Florence (1537): Chosen by Florence’s governing elites, initially as a compromise candidate.

- Subjugation of Siena (1555): Expanded Medici control across Tuscany.

- Grand Duke of Tuscany (1569): Title granted by Pope Pius V. The first Grand Duke in Tuscany’s history.

With this, the Medici became sovereign rulers. Their political power had reached its peak.

Cosimo I created institutions that still shape the city today. His most important achievement was the Uffizi, originally conceived as an administrative headquarters. By bringing magistracies under one roof, Cosimo created a more centralised, manageable bureaucracy.

Other reforms included revitalising textile industries, strengthening the port of Livorno to attract trade, commissioning military and civic works, and encouraging scientific and cultural academies.

This was a new style of Medici governance: not merchant pragmatism (Giovanni), nor republican subversion (Cosimo the Elder), nor cultural splendour (Lorenzo), but straightforward state-building.

Seven generations of Grand Dukes held Tuscany from 1537 to 1737. But the strength of the early Grand Ducal period did not last.

Ritual, Inertia, and Dynasty Exhaustion

After Cosimo I and his son Ferdinando I, the Medici court became increasingly ceremonial. Later Grand Dukes inherited the state but lacked the capacity or energy to renew it.

Key features of the decline included:

- rigid court culture replacing Cosimo I’s administrative dynamism,

- narrow marriage alliances leading to genetic fragility,

- insularity and retreat from broader European affairs,

- dwindling economic relevance as trade routes shifted and competition grew.

By the late seventeenth century, Tuscany was no longer a powerhouse. The Grand Ducal title still carried prestige, but the vitality that had defined earlier Medici leaders was diminished.

Gian Gastone, the seventh and final Grand Duke, was intelligent but withdrawn. His marriage produced no children, and he spent much of his rule in ill health and melancholy. Court life decayed, revenues slackened, and the dynasty approached extinction.

The Last Heir and Saving a Legacy

With the death of Gian Gastone in 1737, the direct Medici male line came to an end. Tuscany passed, by European agreement, to Francis Stephen of Lorraine, the husband of Maria Theresa of Austria. The political structure that Cosimo I had created — the Grand Duchy of Tuscany — now moved into the hands of another dynasty. Yet this shift was not entirely a rupture. The Medici and Habsburg houses had been linked through marriage for generations, most notably through Maria Maddalena of Austria, who married Cosimo II. In this light, the 1737 succession to Francis Stephen of Lorraine can also be seen as the final step in a long-standing dynastic connection.

By name, only one Medici remained: Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici, the Electress Palatine, daughter of Cosimo III and sister of Gian Gastone. She had no children. There would be no continuation through a junior line. What she had instead was something even more powerful: time, clarity, and control over the Medici patrimony.

Where her ancestors sought permanence through banks, political structures, or princely titles, Anna Maria Luisa sought something different. She understood that wealth dissolves and political power passes, but culture, when anchored properly, can outlast every successor.

Her final act would guarantee that the Medici name survived long after the family itself disappeared.

Immediately after Gian Gastone’s death, the new Habsburg-Lorraine rulers gained the right to all Medici estates and collections. In almost every European succession, such patrimony was dispersed, sold, or absorbed into the new dynasty’s holdings.

Anna Maria Luisa prevented this with legal precision. In 1737, she negotiated and executed the Patto di Famiglia (Family Pact), a binding legal agreement between herself and the new rulers of Tuscany. It contained one central condition:

All Medici artworks, libraries, jewels, scientific instruments, archives, and collections must remain in Florence “for public ornament, for the benefit of the people, and to attract the curiosity of foreigners”.

This covenant achieved several things at once: it prevented looting, dispersal, or dynastic appropriation, legally froze the collections inside Tuscany’s borders, redefined the Medici heritage as a public trust, and made Florence the permanent home of one of the world’s greatest cultural patrimonies.

Anna Maria Luisa died in 1743. With her death, the Medici dynasty ended. Yet her signature on the Patto di Famiglia meant that the Medici name would remain synonymous with art, science, humanism, and ingenuity. Her legacy is visible every day in the tens of thousands of visitors who walk through the Uffizi, San Lorenzo, and the Pitti Palace. It is visible in the museums, archives, manuscripts, sculptures, and paintings safeguarded by her decision.

The Four Abundances: A Medici Analysis

The Medici story spans three centuries, a shift from merchants to monarchs, and a final transformation into cultural custodians. Seen through the Four Abundances — Wealth, Relationships, Time, and Purpose — a clearer pattern emerges: the family’s strengths were exceptional, but their vulnerabilities were always baked into the structure.

Wealth

Under Giovanni di Bicci and Cosimo the Elder, wealth was disciplined, diversified, and strategically reinvested. The Medici Bank became Europe’s central transfer engine because it was built on a decentralised partnership structure, a strong core in Florence, and an unrivalled Papal account. This was financial abundance created through prudence.

But over time, that wealth became distorted. The Bank’s balance sheet shifted from merchant credit to political loans. Branches in London and Bruges extended credit to sovereigns whose default risk could not be controlled. By Lorenzo’s era, the Bank had become an informal treasury for Florence, and the cushioning structure that Giovanni designed was weakened from within.

Commercial wealth, once the foundation of Medici influence, became the casualty of political ambition. After 1494, this form of wealth disappeared. With the rise of Pope Leo X and Pope Clement VII, the family rebuilt its power not through assets but through access. Papal authority opened a path back to Florence, culminating in a hereditary dukedom under Cosimo I.

This was a different kind of abundance: prestige, sovereignty, territory, and institutional command. But political wealth is fragile. It depends on external forces — imperial favour, dynastic marriages, geopolitical tides. By the late seventeenth century, the Medici Grand Dukes held a title without momentum.

Anna Maria Luisa redefined Medici abundance entirely. In the Patto di Famiglia, she institutionalised artistic and scientific patrimony as a public asset. The family’s legacy shifted from private holdings to collective heritage.

This cultural wealth has proven the most resilient. Florence is still shaped by Medici taste, Medici commissioning, Medici archives, and Medici governance of culture. The family’s final abundance was the one that survived.

Relationships

Giovanni and Cosimo maintained tight inner circles based on trusted partners, aligned patricians, and carefully cultivated civic relationships. Their network was horizontal: merchants, artisans, clergy, scholars.

Cosimo transformed relationships into political capital. He built loyalty by manipulating electoral processes, rewarding allies through favourable tax assessments, and financing public works that benefited Florentine identity. Cosimo used relationships as a governance mechanism.

Lorenzo’s relationships were broader — artists, diplomats, nobles — but less disciplined. His charisma built goodwill, but his attention moved outward. The internal relational structure weakened: some branches were run by unqualified or overly ambitious relatives, bank managers developed independent agendas and oversight frayed because the family head was preoccupied with diplomacy. Relationship abundance became relational fragility.

During the princely period, the family’s relationships shifted to imperial courts, the Church hierarchy and foreign dynasties. These alliances kept power intact, but introduced dependence. The Medici dynasty now relied on European politics rather than commercial networks.

Anna Maria Luisa had no heirs and no direct political influence. Her covenant with the Habsburg-Lorraines was transactional but visionary. This single negotiated relationship preserved the Medici name for centuries.

Time

The Medici demonstrate how time preferences shape destiny. Their horizon was long. They built systems that created compounding benefits, reputational consistency, steady accumulation of trust, and slow-burning political influence. They understood that stability results from patience.

Lorenzo’s vision of Florence was grand and heartfelt, but the timeline of artistic creation clashed with the timeline of commercial risk. Time abundance here became time pressure.

Once Florence became a hereditary principality, time slowed down to a crawl: courtly ritual replaced momentum, reforms lost urgency and decay accumulated quietly. The Medici lost their commercial responsiveness and their political dynamism.

Anna Maria Luisa’s horizon was the longest of all. She thought not in decades, but in centuries. The Patto di Famiglia was crafted for people she would never meet, in a city she hoped would remember the Medici not as rulers or bankers, but as custodians of beauty. This was time abundance converted into legacy.

Purpose

Purpose shifted dramatically across generations:

- Giovanni (G1) – Purpose rooted in craft, prudence, and stability. A banker who valued reputation over spectacle.

- Cosimo (G2) – Purpose anchored in civic identity. Florence’s greatness became a Medici project.

- Lorenzo (G3) – Purpose shaped by beauty, culture, and diplomacy. The Medici became symbols of refinement and humanism.

- Papal Medici (G4) – Purpose reconstructed as restoration. Spiritual authority used to restore political dominance.

- Cosimo I and Grand Dukes – Purpose recast as sovereignty. The family sought legitimacy through hereditary rule.

- Anna Maria Luisa (G7) – Purpose distilled to remembrance.

Across Wealth, Relationships, Time, and Purpose, a consistent pattern emerges: strength in one phase created blind spots in the next. Each succession reset the definition of “Medici success”.

The Family Council Canvas: A Counterfactual Look

The Medici dynasty is often framed through art, politics and power, but at its core, it faced the same structural tensions as any modern family enterprise: concentration of risk, uneven preparation across generations, unclear decision-making boundaries, and the absence of a shared, long-term narrative. Using the Family Council Canvas (FCC), we can identify three phases where a structured governance process might have stabilised the dynasty’s evolution.

Dynamics

A Family Council would have surfaced the tensions that accumulated quietly across generations. For the Medici, these included unclear boundaries between the Bank and the State. Over time, the financial and political systems merged without an explicit decision. A Canvas discussion would have forced the family to address:

Is the Bank a private enterprise or the financial arm of Florence?

What level of political lending is acceptable?

Should sovereign exposure require collective approval?

Had these questions been formalised, the Bank would not have drifted from merchant credit to political credit without a structural safety net.

Cosimo ruled through influence; Lorenzo through charisma; the Grand Dukes through title. Yet none of them operated within a defined decision-making framework. The FCC would have clarified decision rights, responsibilities of non-operating family members, expectations of heirs before entering leadership, and the boundaries between family authority and external advisors. Instead, the family relied on the capacity of each successor, creating a governance system that collapsed whenever a less capable heir inherited power.

Medici history is filled with factionalism: the senior line vs cadet branches, competing ambitions, and occasional betrayals. Without a forum for alignment, tension moved underground. The FCC would have provided structured dialogue, reducing the cycles of exile, restoration, and revenge.

Compass

The Medici’s purpose shifted dramatically across generations. The absence of a shared compass meant that each generation redefined the mission without reference to those before. A Canvas process would have asked:

What is the enduring purpose of Medici stewardship?

Is political power the goal, or a tool?

Should the family prioritise Florence, the Bank, or the cultural fabric of the city?

Which values are non-negotiable across generations?

If “cultural custodianship” had been named early, the later decline might have been transformed into a planned transition rather than an accidental collapse.

Journey

Florence knew the Medici story; the Medici did not always know it themselves. The family’s own internal narrative remained implicit, not documenting the lessons from Giovanni’s decentralised bank, Cosimo’s strategy of ruling without office, Lorenzo’s cultural vision and its financial consequences, the impact of political lending, and the reasons behind the exile and return. An FCC journey would have turned these episodes into explicit institutional memory:

“What did each generation protect, and what did it sacrifice?”

Without this narrative, later Medici rulers inherited power without understanding its architecture, its vulnerabilities, or its trade-offs.

Goals & Actions

If the FCC had existed, several tangible policies might have reshaped the dynasty’s development.

A Governance Framework for the Bank

- A clear line separating commercial credit from political loans.

- A requirement for central oversight of branch managers.

- Criteria for appointing or removing partners in distant branches.

- A cap on sovereign exposure.

This alone might have prevented the catastrophic failures of London and Bruges.

Succession Criteria for Family Leaders

The Medici repeatedly placed sons in leadership without formal preparation:

- Piero “the Gouty”: capable but too ill to manage a complex system.

- Lorenzo: brilliant but distracted.

- Piero “the Unfortunate”: unprepared for political crisis.

- The Grand Ducal heirs: often insufficiently trained to manage a state.

A Canvas-based succession policy might have required:

- political or commercial apprenticeships,

- external experience,

- capability reviews,

- and clear role definitions.

This would have replaced hereditary assumption with structured readiness.

A Family Constitution for the Transition to Monarchy

When Florence became a hereditary duchy under Cosimo I, the family lacked a framework to manage this new form of power. An internal constitution would have clarified:

- the rights of cadet branches,

- expectations for heirs,

- protocols for foreign marriages,

- standards for court governance,

- and boundaries between personal authority and state authority.

This would have reduced later courtly stagnation and internal fracturing.

Cultural Stewardship as a Named Strategic Priority

If the Medici had consciously framed themselves as guardians of Florence’s artistic and scientific heritage from the start, the Patto di Famiglia would not have been an emergency measure at the dynasty’s end, but a natural institutional evolution. This shift could have begun generations earlier.

Governance Lessons for 21st-Century Family Enterprises

The Medici dynasty presents an extraordinary historical arc: a family that built the most influential bank of the fifteenth century, shaped the politics of Florence, produced two popes and seven grand dukes, and concluded its story with a great cultural legacy. For modern families, the Medici offer more than historical charm.

Below are the three enduring lessons.

Lesson 1: Governance Must Grow with the Enterprise

The early Medici succeeded through architecture. Giovanni di Bicci’s decentralised partnerships insulated each branch from the others. Cosimo the Elder consolidated power through networks and incentives. Their model worked as long as leadership remained vigilant.

But the structure never matured into an institution. It never evolved from personality-led oversight to structured compliance, individual authority to collective decision-making, and apprenticeship to formal preparation.

This became fatal when Lorenzo’s attention shifted to diplomacy and art. Without an institutional backbone, a system built on personal discipline could not withstand dispersed risk.

As a modern comparison, the Brenninkmeijer family shows the opposite trajectory. As their ownership group grew to over 500 members, governance became more formal, separating. Medici governance remained frozen at the scale of Giovanni and Cosimo, even as their responsibilities expanded from banking to statecraft. The lesson is clear: If the structure does not evolve, success becomes fragile.

Lesson 2: Commercial Capital Must Be Insulated from Political Risk

The Medici Bank’s downfall began long before 1494. It began the moment the family allowed political loyalty to override fiduciary judgment. The Papal account — brilliant at first — pulled the Bank into high-risk sovereign exposure, illiquid loans used for diplomacy, and blurred lines between Florence’s treasury and Medici capital.

By Lorenzo’s era, the Bank was treated as a public purse. The commercial system was simply not designed to absorb political shocks: kings defaulted, dukes fell in battle, and branch managers made loans that no commercial partner would have approved.

In contrast, the Rupert family offers a demonstration of disciplined separation: Richemont is placed in Switzerland for stable luxury expansion, Remgro is ring-fenced from South African political exposure, and Reinet is used to isolate and ultimately exit the BAT legacy asset. This is the precise opposite of what happened under the Medici. Lorenzo tied the Bank to the fortunes of states, and when those states faltered, the Bank collapsed.

The modern takeaway: Never allow political, emotional, or reputational obligations to compromise the balance sheet.

Lesson 3: Succession Requires Competence, not Potential

Many Medici heirs were gifted, but few were prepared. Across two centuries, succession repeatedly depended on birth order rather than readiness. Piero “the Gouty” was too ill to oversee a sprawling bank. Lorenzo “the Magnificent” was charismatic but allowed oversight to disintegrate. Piero “the Unfortunate” inherited a crisis he was unequipped to manage. Several Grand Dukes lacked the energy or judgment needed to govern a state.

Biological succession ultimately ended the dynasty altogether. When potential leaders are placed into high-stakes roles without formal preparation, the system becomes vulnerable to individual limitations. Modern families that endure treat succession as a long apprenticeship: capability reviews, external experience, merit-based entry criteria, clear governance roles, and separation between ownership and management.

The Medici never institutionalised any of this. Their model relied on talent appearing by chance. When it did not, the structure faltered. The lesson is timeless: Inheritance may grant title, but only competence sustains a dynasty.

Conclusion

The Medici story spans three centuries of ingenuity, ambition and reinvention. It shows how far a family can go when talent aligns with opportunity — and how vulnerable a dynasty becomes when structure does not keep pace with scale.

Yet the final chapter alters the meaning of the whole narrative. Anna Maria Luisa did not cling to titles or mourn what the family had lost. She focused instead on what could still be protected. By securing the Medici collections for Florence, she ensured that the family’s name would live on through the works they had commissioned, studied and loved.

Her decision reminds us that succession is not only about who follows next, but also about what is meant to endure. Families rarely control every turn of fortune, but they can decide how their story is carried forward. In the end, Anna Maria Luisa achieved what the Medici banks, political networks, and titles could not: permanence.

Disclaimer: This article is a case study based on publicly available information and is intended for educational and informational purposes only. The analysis and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not constitute factual claims about the private lives or intentions of the individuals discussed. The use of any copyrighted material is done for the purposes of commentary and criticism and is believed to fall under the principles of fair use. All images are used with attribution to their known sources.

Sources:

Belleten (n.d.). The Medici family became the bankers of the Christian Pope, especially during the times of the two Medici Popes, Pope Leo X and Pope Clement VII. Available at: https://belleten.gov.tr/tam-metin/3645/eng (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Britannica (n.d.). Cosimo de’ Medici. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cosimo-de-Medici (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Depledge SWM (n.d.). The Medicis: The Banking Family at the Heart of the Renaissance. Available at: https://www.depledgeswm.com/the-medicis-the-banking-family-at-the-heart-of-the-renaissance/ (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

De Roover, R. (1963). The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank, 1397–1494. Available at: https://eprints.illc.uva.nl/id/document/978 (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu (n.d.). Cosimo de’ Medici: Patronage, Persona, and the Establishment of a Dynasty. Available at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1068&context=exposition (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Ebsco (n.d.). Cosimo de’ Medici. Available at: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/cosimo-de-medici (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Ebsco (n.d.). Lorenzo de’ Medici. Available at: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/lorenzo-de-medici (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

High Speed History (2023). The Medici Bank. Available at: https://highspeedhistory.com/2023/04/24/the-medici-bank/ (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Wikipedia (n.d.). Medici Bank. Available at:(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medici_Bank) (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Laphams Quarterly (n.d.). Arts Endowment. Available at: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/about-money/arts-endowment (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

LitCharts (n.d.). Cosimo de Medici Quotes in The Life of Galileo. Available at: https://www.litcharts.com/lit/the-life-of-galileo/characters/cosimo-de-medici (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Lorenzo de’ Medici on love and beauty (n.d.). Available at: https://www.italianrenaissanceresources.com/units/unit-2/sub-page-03/lorenzo-de-medici-on-love-and-beauty/ (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

McLean, P.D. (n.d.). What the Rise of the Medici Tells Us About Social Networks and Political Action. Available at: https://medium.com/point-of-decision/what-the-rise-of-the-medici-tells-us-about-social-networks-and-political-action-3f52c3f0bc72 (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Medium (n.d.). Patrons and Propaganda. Available at:(https://medium.com/@SISBlog_TheMedicis/patrons-and-propaganda-4f00b7c8446f) (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Nuitalian.org (2022). The Art of Rule: The Medicis’ Key to Power. Available at: https://nuitalian.org/2022/12/13/the-art-of-rule-the-medicis-key-to-power/ (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Palladium Magazine (2025). The Medici Method. Available at: https://www.palladiummag.com/2025/11/07/the-medici-method/ (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

SMA.unifi.it (n.d.). Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici. Available at: https://www.sma.unifi.it/vp-518-anna-maria-luisa-de-medici.html (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Toomasolev.com (n.d.). Devastating Financial Crises in Family-Owned Businesses. Available at: https://toomasolev.com/devastating-financial-crises-in-family-owned-businesses/ (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Wikipedia (n.d.). Cosimo de’ Medici. Available at: https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Cosimo_de’_Medici (Accessed: 3 December 2025).

Wikipedia (n.d.). House of Medici. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Medici (Accessed: 3 December 2025).