A critical question often emerging in families is how our children can be introduced to the complexities of the family’s assets and responsibilities without being overwhelmed or fostering a sense of entitlement. While common advice suggests a gradual introduction, starting with the sharing of financial documents and then delving into more details as an interest arises, this is only a starting point.

The greatest risks in intergenerational wealth transfer are rarely financial; they are human. Studies reveal a startling rate of attrition, with some showing that only 3-5% of family businesses survive to the fourth generation. An Ernst & Young survey identified the primary reasons for these failures as communication challenges (60%), inadequate preparation of the next generation (25%), and an undefined purpose for the family’s wealth (12%).

Success requires a deliberate, psychologically informed framework that focuses on human development, not just information transfer. It is a journey that reframes wealth as a tool for responsibility and cultivates capable stewards over time.

The Psychological Hurdles of Inherited Wealth

Successfully navigating wealth transfer requires acknowledging the profound psychological challenges that both grantors and heirs face.

- Stewardship vs. Entitlement: A primary concern for parents is raising children who view wealth with a sense of responsibility rather than as an unearned privilege. Entitlement can stifle motivation, while a stewardship mindset fosters the long-term thinking necessary to preserve and grow family capital.

- The Quest for Identity: For an heir, significant wealth can complicate the search for personal identity and purpose. When financial security is a given, the motivation to find meaning can become a struggle. Heirs may feel inadequate compared to their successful predecessors or feel an “oppressive obligation” to live up to the family name.

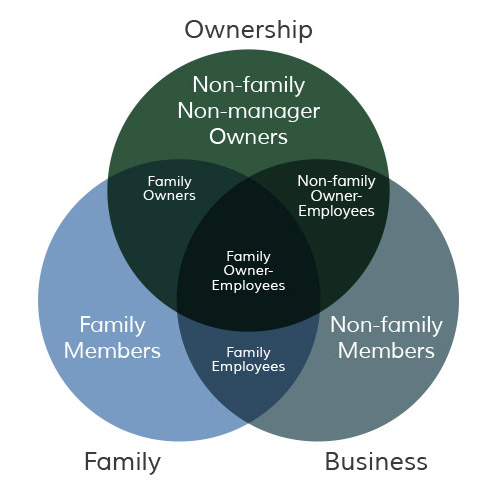

- Family Dynamics: A lack of open communication and intra-family mistrust are among the most significant factors in the failure of family businesses. The family environment is the crucible where financial attitudes are formed. Furthermore, families and businesses operate on different principles — the family on an emotional and egalitarian logic, and the business on a rational and meritocratic one. This tension can create conflict if not managed explicitly.

A Phased Framework for Cultivating Capable Stewards

To navigate these challenges, a comprehensive, phased approach is essential, one that deliberately sequences education, experience, and responsibility to ensure that readiness precedes authority.

Phase 1: Foundational Values & Financial Literacy (Early Adulthood)

This initial phase focuses on building character and context long before complex financial details are introduced. The goal is to cultivate a sense of responsibility by starting with a foundation of values and history. Education should begin by actively sharing the family’s culture and mission, using storytelling and mentorship to build a shared narrative. This naturally leads to direct conversations about the purpose of wealth, contrasting a stewardship mindset with entitlement and emphasising that inheritance is connected to responsibility, not dependency.

These values are made tangible through practical application. Introducing basic financial literacy, such as budgeting and investment principles, provides a necessary foundation. A tool like the “Three-Circle Model” can be used to help heirs understand the distinct but overlapping systems of Family, Business, and Ownership. A powerful way to reinforce these lessons is through early and active involvement in the family’s philanthropic efforts. This hands-on giving acts as a practical classroom for connecting wealth to family values and teaching financial stewardship.

TAGIURI AND DAVIS, 1982

The Three-Circle Model of the Family Business System was developed by Renato Tagiuri and John Davis at Harvard Business School, and was circulated in working papers starting in 1978. It was first published in Davis’ doctoral dissertation, The Influence of Life Stages on Father-Son Work Relationships in Family Companies, in 1982. In 1996, the Family Business Review published it in Tagiuri and Davis’ classic article, “Bivalent Attributes of the Family Firm.”

Phase 2: Integration & Experiential Learning

This phase transitions from abstract values to tangible experience. The primary goal is to build practical skills and promote “psychological ownership” — the deep, personal feeling of accountability that comes from direct involvement and contribution. This is the time for hands-on engagement through structured internships, either within or outside the family company, which serve to build both skills and self-confidence. This practical education can be supported by formal mentorship from senior family members, management, or trusted advisors who share invaluable guidance and experience.

This experiential learning is deepened with more advanced educational topics. Heirs should receive education on the business’s strategy and operations to understand how things work. It is also critical to introduce formal policies for constructive conflict resolution to mediate disagreements before they escalate. To support this, families can adopt advanced educational approaches like “Whole-Person Learning,” which uses coaching and self-reflection exercises to develop emotional and social intelligence alongside cognitive skills. This stage can also involve participation in governance, for instance by having the next generation sit in as non-voting observers in family council or board meetings to see how decisions are made.

Phase 3: Stewardship & Active Participation

This final phase marks the full transition to active, informed, and influential participation and prepares the next generation for significant leadership and ownership roles. Their involvement becomes more sophisticated as they grapple with advanced topics like strategic planning and complex governance structures. The education here involves a deep dive into how the family, ownership, and business systems are coordinated and how to manage the logistical challenges that arise as a family grows. This includes treating succession not as a single event, but as a long-term strategic process with clear, transparent criteria.

The corresponding activities are high-level and consequential. Heirs are now prepared to take on active, voting roles on family councils, committees, or advisory boards. They may also begin working directly with external consultants on complex issues like conflict mediation and strategic planning. A critical activity in this phase is direct participation in developing or updating the family constitution. The collaborative process of creating this document—the debates, discussions, and exchange of expectations—is often more important than the final text, as it builds the family’s collective problem-solving skills and ensures genuine commitment to the outcome.

The Role of Family Governance

This entire framework is powered by robust family governance structures that provide the formal forums for communication, education, and decision-making.

- The Family Constitution: This key document explicitly states the family’s values, goals, and rules on crucial topics like conflict management and successor qualifications. Its power is moral and relational, derived from the collaborative process of its creation and the shared commitment it represents.

- The Family Council: This body is a crucial mechanism for building consensus, planning the education of heirs, and promoting engagement. It provides the formal channel for planned communication that fosters a sense of togetherness and improves equality among the next generation.

From a Difficult Question to a Deliberate Process

The answer to the dilemma is to reframe the task treat is as a long-term curriculum instead of a single briefing; a cultivation of character, not a data transfer. Families can systematically build the competence, confidence, and commitment required for true stewardship by guiding the next generation through a deliberate path of learning, experience, and responsibility. This relentless focus on contribution and shared purpose transforms the concept of inheritance from a passive prize into an active responsibility