For most institutions, succession is a moment of risk. For the Ismaili Imamat, it is the mechanism through which continuity is proven. The Aga Khan is not the head of a state, yet he signs treaties. Not a corporate leader, yet oversees a global network spanning development, finance, culture, and education. Not an elected figure, yet commands allegiance across continents.

For over fourteen centuries, authority has passed from one Imam to the next without territory, without interruption, and without fragmenting the institution itself. In a world where dynasties dissolve, and organisations fracture under scale, the Imamat has done the opposite: it has grown more structured, more legible, and more durable with each transition.

This case study examines how succession works under spiritual authority and institutional governance, and what that reveals about permanence in the modern world.

Leaving Territory to Preserve Authority

The modern history of the Ismaili Imamat begins, surprisingly, with withdrawal. For centuries, the Imam’s authority had been exercised under varying degrees of tolerance and constraint within Persian political life. By the early nineteenth century, that arrangement had become untenable. What was at stake was not land or office, but the independence of the Imamat itself.

When Hasan Ali Shah succeeded his father as Imam in 1817, he did so as a teenager in a volatile political environment. Initially aligned with the Qajar court, he was appointed governor of Qumm and later Kirman. These roles offered status, but they also bound the Imamat to court politics, factional rivalry, and shifting loyalties that threatened the autonomy of a hereditary spiritual office.

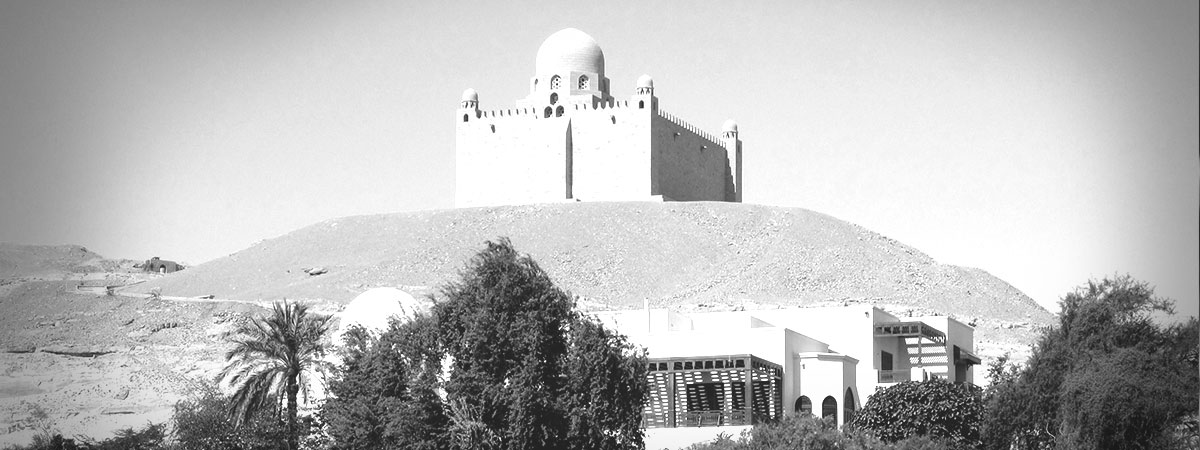

Conflict was inevitable. Political manoeuvring turned into open confrontation, imprisonment, and the realisation that remaining embedded in territorial power carried an existential risk. In 1841, the Imam made a decisive choice: he left Persia.

This migration was not an exile in the usual sense. It was a strategic disengagement from territorial sovereignty. By moving first through Afghanistan and eventually to the Indian subcontinent, the Imamat stepped out of a centuries-old pattern of dependence on local rulers and into a new legal and political environment shaped by imperial administration, contract law, and international recognition.

In British India, the Imam encountered a system that valued order, legal clarity, and loyalty over dynastic intrigue. His services to the colonial administration during military campaigns in Sindh and the northwest frontier earned him formal recognition as “His Highness.” More importantly, they established a precedent: the Imamat could operate as a distinct authority within, but not subordinate to, a state system.

This was the first decisive governance shift in the modern Imamat’s history. Authority was no longer anchored in territory or court appointment. It was beginning to be expressed through legal status, communal allegiance, and negotiated recognition.

The move also changed the relationship between the Imam and his followers. The community was no longer clustered around a geographic centre. It became diasporic by necessity, bound together by allegiance rather than proximity. This condition would later become one of the Imamat’s greatest strengths.

What appeared, from the outside, as retreat was in fact consolidation. By relinquishing territory, the Imamat preserved continuity. By exiting court politics, it created the conditions for a form of leadership that could survive empire, decolonisation, and the modern nation-state.

Everything that followed — legal battles, institutional growth, diplomatic recognition, and orderly succession — rests on this early decision to protect authority by letting go of land.

From Personal Authority to Legal and Institutional Order

Once the Imamat relocated to British India, succession was no longer only a spiritual matter. It became a question of governance, law, and the management of a dispersed community operating within modern political systems. Each succession that followed introduced a new layer of structure, gradually transforming a charismatic, person-centred authority into an institution capable of surviving scale.

Aga Khan I: Recognition Through Law and Alliance

Hasan Ali Shah’s authority in India rested initially on personal allegiance and inherited legitimacy. Yet as his role expanded, so did resistance from within the community itself. Questions arose over religious dues, communal assets, and the limits of the Imam’s temporal authority.

These tensions culminated in the 1866 Aga Khan Case in the High Court of Bombay. The ruling did more than settle a theological dispute. It provided legal confirmation that the Imam held absolute authority over communal property and religious contributions. Succession, from that point forward, was not only a matter of lineage; it was anchored in jurisprudence.

This moment marked a decisive governance shift. Authority was no longer dependent on custom alone. It was now enforceable through modern legal systems.

Aga Khan II: Continuity Without Expansion

The second Aga Khan’s tenure was brief, but stabilising. His focus lay inward, strengthening education and reinforcing communal cohesion rather than pursuing external influence. Importantly, this period normalised succession as an orderly transition rather than a moment of crisis.

The Imamat demonstrated that leadership could pass smoothly even without dramatic reform or expansion. This set a precedent for continuity through restraint.

Aga Khan III: Reform, Representation, and Global Standing

With Aga Khan III, succession took on a new public dimension. His long Imamat coincided with the decline of empires and the rise of modern nation-states. Rather than retreat, he positioned the Imamat as a legitimate interlocutor on the world stage.

Governance under his leadership expanded beyond the community. Education, legal reform, women’s rights, and political advocacy became tools for strengthening both internal cohesion and external legitimacy. His role in international diplomacy reinforced the idea that the Imamat could operate as a moral authority without territorial power.

Succession, during this period, became associated with modernisation. Each generation was expected not merely to preserve authority, but to reinterpret it in light of changing conditions.

Aga Khan IV: Institutionalisation as a Succession Strategy

The 1957 succession introduced a fundamental break with convention. Aga Khan III bypassed his sons and named his grandson as successor, citing the need for leadership attuned to a rapidly changing world. This decision underscored a crucial principle: succession served the continuity of the office, not familial expectation.

Under Aga Khan IV, governance shifted decisively from personality to institution. The creation of the Aga Khan Development Network formalised what had previously existed as dispersed initiatives. Authority was delegated, professionalised, and embedded in organisations capable of operating across jurisdictions.

This institutional architecture reduced the risks traditionally associated with succession. Leadership change no longer implied operational disruption. The Imam remained the source of strategic authority, but execution was distributed across legally independent entities with professional management.

Over time, the Imamat evolved into a layered system: spiritual leadership at the centre, surrounded by legal, economic, and development institutions designed to absorb change without fragmentation. Succession, in this model, ceased to be a vulnerability and became a mechanism for renewal.

Continuity Without Disruption

The transition of February 2025 did not feel like a rupture. That, in itself, is the result of deliberate design. When Aga Khan IV passed away in Lisbon, the mechanisms of succession were already in place. The principle of Nass — the explicit designation of a successor by the sitting Imam — removed uncertainty. Authority did not pass through negotiation or contest, but through a process the community understood as both spiritual and constitutional.

Prince Rahim Aga Khan was named the 50th Imam in his grandfather’s Will, unsealed the day after his death. The formal accession ceremony, the Takht Nashini, took place in Lisbon shortly thereafter, where he assumed the office of Imam-of-the-Time and received pledges of allegiance from Ismaili institutions across the world. What distinguished this succession from earlier ones was not its legitimacy, but its ease.

Why the 2025 transition held

Several factors contributed to the stability of the handover. First, authority had long since been separated from day-to-day execution. The Imamat no longer relied on the personal intervention of the Imam to function. Institutions continued operating without pause, guided by established mandates and professional leadership.

Second, the successor was already embedded in governance. Prince Rahim had spent years overseeing environmental, economic, and sustainability initiatives within the development network. He entered the Imamat with operational knowledge rather than symbolic preparation alone.

Third, the family itself functions as a governing layer. Senior roles held by siblings and close relatives form a cabinet-like structure that distributes responsibility across policy, education, culture, and external relations. Succession does not concentrate power in a single pair of hands; it activates a collective.

A shift in emphasis, not direction

Early guidance from the new Imam signalled continuity in purpose with a change in emphasis. Where the previous generation prioritised institutional build-out and physical infrastructure, the new leadership has placed greater weight on environmental resilience, climate adaptation, and digital capacity.

This is not a departure from the Imamat’s mandate, but an update of its operating logic. The improvement of quality of life now requires different tools than it did in the mid-twentieth century.

The key point is structural: the institution absorbed generational change without destabilisation. Authority transferred cleanly because it was never entangled with personal ownership, informal networks, or unspoken expectations. Succession worked because it had been treated, for decades, as a governance problem rather than a family matter.

The Four Abundances

The Aga Khan Imamat offers a rare example of abundance sustained without ownership of land, without a state, and without personal control over assets. Its resilience lies in how each abundance has been deliberately separated, protected, and recombined at the institutional level.

Wealth

The Imamat’s approach to wealth is defined by separation. Personal wealth held by the Imam — inherited estates, private business interests, and cultural assets — is legally and operationally distinct from institutional resources. Funds belonging to the Imamat derive from religious offerings and from the reinvested surpluses of its development agencies.

This separation removes one of the most common sources of dynastic failure: the blurring of personal entitlement and fiduciary responsibility. The economic engine of the system sits within the development network’s for-profit arm, whose surpluses are reinvested rather than extracted. Wealth functions as fuel for the mission, not as a reward for office. That distinction has allowed scale without suspicion and growth without erosion of trust.

Relationships

Internal cohesion rests on a form of legitimacy that does not need to be renegotiated with each generation. Succession through Nass provides clarity, while institutional roles distribute responsibility across family members and professionals.

Externally, relationships are built through diplomacy rather than dependence. The Imamat engages with states, multilateral bodies, and civil society as a partner, not a petitioner. This has created a network of trust that substitutes for territorial power.

Crucially, relationships are not personalised. They are held by offices, boards, and institutions, reducing vulnerability when leadership changes.

Time

Few institutions operate with a longer sense of time. The Imamat’s succession line stretches back fourteen centuries, yet its modern structures are designed to survive futures that cannot be predicted. Constitutions, legal agreements, and treaties replace informal understandings. Authority is prepared in advance rather than improvised.

Time is also treated asymmetrically. The spiritual office is continuous; strategies are revisable. This allows adaptation without identity loss, a balance many dynastic organisations fail to achieve. Succession is not an interruption in time, but one of its organising principles.

Purpose

Purpose is the Imamat’s most stable asset. The improvement of quality of life is not framed as charity, nor as reputation management, but as the secular expression of a spiritual mandate. Education, health, culture, and economic opportunity are pursued as long-term obligations rather than short-term programmes.

Because purpose is institutionalised — embedded in charters, agencies, and operating models — it does not depend on the personality of the Imam. Each generation interprets it differently, but none is free to abandon it. This is what allows continuity without stagnation.

How the Canvas Could Have Helped

The Aga Khan Imamat did not lack clarity, discipline, or continuity. In many respects, it already operates as a highly advanced governance system. Applying the Canvas here is therefore not about remedying failure, but about making visible the design choices that have allowed the institution to endure.

Seen through this lens, the Canvas helps articulate why the Imamat works — and where its strengths differ from those of family enterprises rooted in ownership and territory.

Dynamics

The Imamat operates across overlapping domains: spiritual authority, institutional governance, development finance, diplomacy, and family roles. Much of this complexity is absorbed through tradition and theological legitimacy. The Canvas would surface these dynamics explicitly:

- the distinction between spiritual authority and executive power,

- the role of family members as policy stewards rather than heirs to assets,

- the relationship between the Imam and professional leadership within institutions.

By naming these layers, the Canvas would reduce the risk of informal assumptions becoming sources of confusion as scale increases.

Compass

Across centuries, the Imamat has adapted its methods while preserving its mandate. The Canvas Compass would help codify this distinction. It would clarify:

- which principles are non-negotiable (succession through Nass, fiduciary separation, service to humanity),

- which strategies are provisional (development models, geographic focus, operational tools),

- and how ethical boundaries guide engagement with states and markets.

This separation between principle and practice is already present; the Canvas would make it transmissible.

Journey

The Imamat’s history is rich, but its lessons are often carried through oral tradition or institutional memory. The Canvas Journey would translate key transitions into shared reference points:

- the decision to leave Persia,

- the legal consolidation in colonial India,

- the shift from charismatic leadership to institutional governance,

- the move toward supranational recognition in Lisbon.

Documenting the intent behind these shifts strengthens future decision-making, especially when new contexts create unfamiliar pressures.

Goals & Actions

At the operational level, the Canvas would support alignment across a vast ecosystem:

- clarifying mandates between boards, agencies, and senior officials,

- ensuring that growth remains tied to mission rather than momentum,

- reinforcing accountability without undermining trust.

In this context, the Canvas acts less as a corrective tool and more as a mirror, reflecting how long-term stewardship can be structured when authority is separated from ownership and purpose is embedded institutionally.

What the Case Teaches Family Offices

The Aga Khan Imamat is not a family business, yet it confronts many of the same questions that challenge multigenerational enterprises: how authority is transferred, how assets are governed, how purpose survives scale, and how legitimacy is maintained across borders and time.

Its answers are instructive precisely because they differ from conventional models.

1. Succession is strongest when it serves an office, not individuals

In the Imamat, succession does not reward seniority, popularity, or entitlement. It serves continuity of the role itself. The principle of Nass makes clear that the purpose of succession is institutional stability, not familial symmetry.

For family offices, the lesson is not to adopt hereditary designation, but to ask a similar question:

“What exactly is being succeeded — wealth, control, purpose, or responsibility?”

When this remains vague, succession becomes contested.

2. Separating authority from assets reduces conflict

One of the Imamat’s most effective safeguards is the strict separation between the Imam’s personal wealth and the resources held in trust for the community. This prevents the conflation of leadership with entitlement. Authority carries responsibility, not extraction rights.

Family offices that blur this line often struggle with disputes over fairness, compensation, and control. The Imamat shows that clarity at the boundary can remove many of these tensions before they arise.

3. Institutions scale better than personalities

The Imamat survived decolonisation, geopolitical upheaval, and global expansion by moving authority into institutions early. Boards, agencies, constitutions, and treaties absorbed complexity that no individual could manage alone.

Families that rely too heavily on charismatic founders or informal consensus often find succession destabilising. Professional structures do not weaken legacy; they preserve it.

4. Legal recognition can substitute for territorial or ownership power

By securing a supranational legal status, the Imamat achieved stability without sovereignty. It operates through agreements rather than control of land or markets.

For global families operating across jurisdictions, this highlights the strategic importance of legal architecture. Stability is often a function of where and how authority is anchored, not how much is owned.

5. Purpose endures when it is institutionalised

The Imamat’s mission is embedded in operating entities, not statements of intent. Education, health, culture, and development are carried forward by organisations with their own mandates and governance.

Family offices that rely on shared values alone often see purpose fade with generational distance. When purpose is operationalised, it survives leadership change.

6. Adaptation does not require abandoning identity

Across fourteen centuries, the Imamat has repeatedly changed form without losing legitimacy. It has treated tradition as a source of continuity, not constraint.

For families facing new technologies, markets, or social expectations, the lesson is clear: continuity depends less on preserving past structures than on preserving the reasoning behind them.

Closing Words

The Aga Khan Imamat endures not because it owns territory, controls markets, or commands political power, but because it has learned how to separate authority from possession and continuity from personality.

Across fourteen centuries, succession has been treated as a structural question rather than a familial event. Authority passes without disruption because it is anchored in office, safeguarded by law, and exercised through institutions designed to absorb change. What appears, from the outside, as exceptional stability is in fact the outcome of deliberate choices made over generations.

The transition to the 50th Imam in 2025 marked a recalibration. Environmental resilience, digital capacity, and global coordination now sit alongside education, health, and culture as expressions of a mandate that remains unchanged in spirit.

For other long-lived enterprises, the Imamat presents an alternative model of continuity. Permanence comes not from accumulation, but from clarity of focus and structures that support renewal across generations. When succession exposes weakness elsewhere, the Imamat demonstrates the strength of governance designed for those who come next.

Disclaimer: This article is a case study based on publicly available information and is intended for educational and informational purposes only. The analysis and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not constitute factual claims about the private lives or intentions of the individuals discussed. The use of any copyrighted material is done for the purposes of commentary and criticism and is believed to fall under the principles of fair use. All images are used with attribution to their known sources.

Sources:

Aga Khan Development Network (2025). Prince Rahim Aga Khan V named 50th hereditary Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. Available at: https://the.akdn/en/resources-media/whats-new/news-release/prince-rahim-aga-khan-v-named-50th-hereditary-imam-of-the-shia-ismaili-muslims (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Aga Khan Development Network (n.d.). Our Approach to Development. Available at: https://the.akdn/en/how-we-work/our-approach/our-approach-to-development (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Aga Khan Development Network (2025). AKDN Pakistan Newsletter Summer Special Edition 2025. Available at: https://static.the.akdn/53832/1760712403-akdn-pakistan-newsletter-summer-special-edition-2025.pdf (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Dawn (2025). Prince Rahim becomes the new Aga Khan. Available at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1891345 (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

G.K. Today (n.d.). Aga Khan III. Available at: https://www.gktoday.in/agha-khan-iii/ (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Ismaili Gnosis (n.d.). Does the Aga Khan’s wealth come from the tithes of his followers?. Available at: https://ask.ismailignosis.com/article/39-does-the-aga-khan-s-wealth-come-from-the-tithes-of-his-followers (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Ismaili Imamat (n.d.). Ismaili Imamat Overview. Available at: https://ismaili.imamat/ (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Ismaili Imamat (2025). 2025 Ismaili Constitution. Available at: https://forum.ismaili.net/viewtopic.php?t=9438 (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Ismaili Mail (2024). Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I’s migration to the Indian subcontinent initiated the modern phase of Nizari Ismaili history. Available at: https://ismailimail.blog/2024/12/03/imam-hasan-ali-shah-aga-khan-is-migration-to-the-indian-subcontinent-initiated-the-modern-phase-of-nizari-ismaili-history/ (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Oxford Public International Law (n.d.). Ismaili Imamat. Available at: https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law-epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e2238 (Accessed: 13 January 2026).

Wikipedia (n.d.). Aga Khan Case. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aga_Khan_case (Accessed: 13 January 2026).